The Roman religion came to include a more personal worship of ancestors and deified Roman rulers. Like the Etruscans, the Romans assimilated many Greek artistic and building practices, along with the Greek state religion. Apollo’s active, almost off-kilter pose represents well the characteristic, fresh liveliness emblematic of Etruscan sculpture, found even in funerary works like the Sarcophagus from Cerveteri. The Etruscans probably knew of these cultures through their continuous trading of natural resources and goods in the Mediterranean. He does borrow aspects from archaic Greek kouroi as well as Near Eastern art.

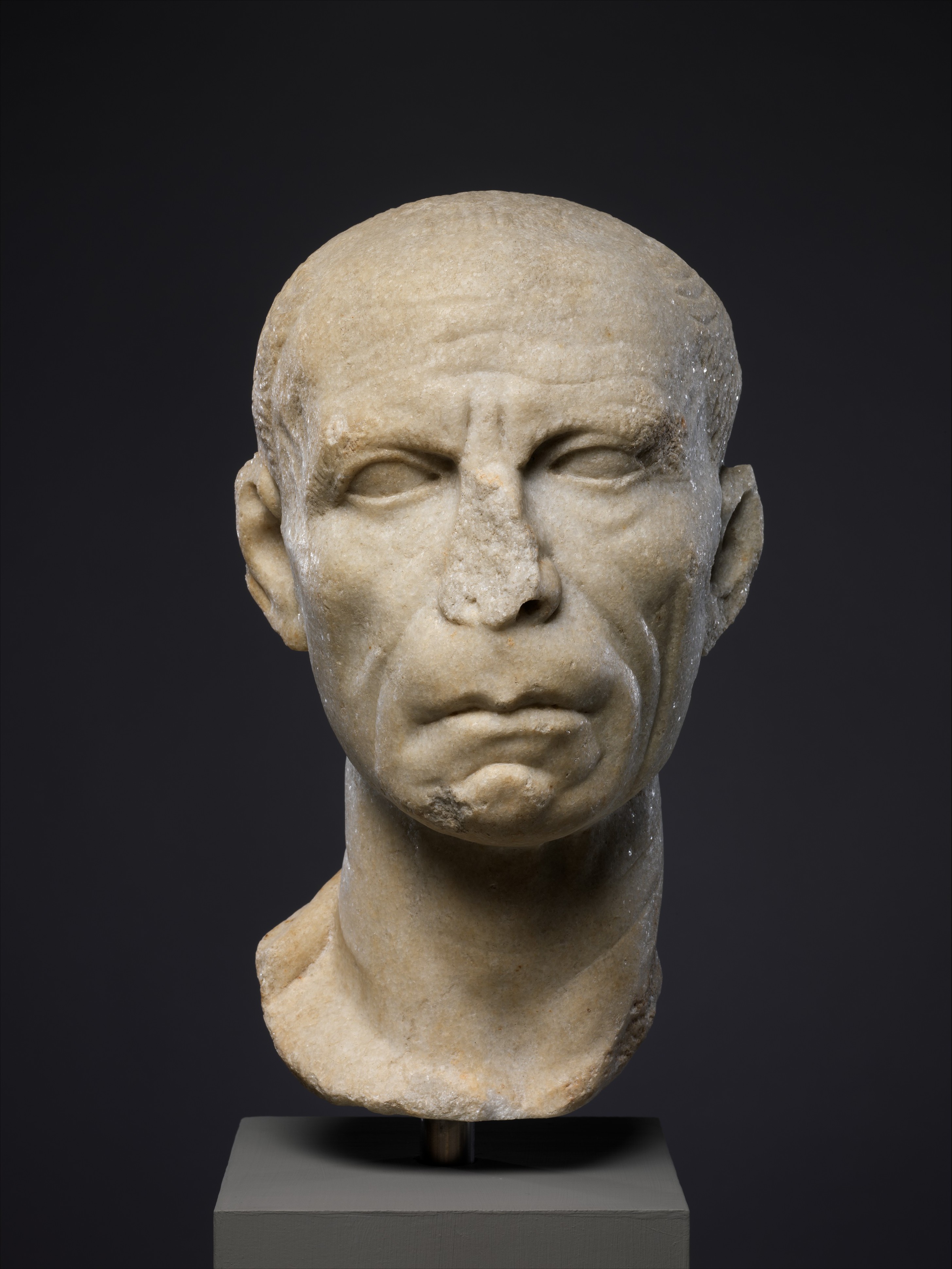

When discussing the life-size terracotta sculptures that surmounted those temples, like the Apollo of Veii, encourage students to think like artists: what might be the technical struggles of working with the material? Imagine trying to maintain the shape of a giant lump of wet clay! Have students compare this work to the contemporary Kritios Boy (Greek, 480 BCE) to find reasons why our Apollo here is certainly NOT from Classical Greece (posture, clothing, proportion, etc.). Although their square temples were built, much like Greek ones your students may have already seen, on platforms using post-and-lintel construction, the Etruscans also used the arch (like the Romans would) to build a barrel vault in at least one instance. At that writing, Vitruvius was already looking five hundred years into the past. He projects Roman ideals of beauty, based on function, strength, and human proportions, back onto Etruscan architecture. Vitruvius’ description of Etruscan temples in his Ten Books on Architecture (20-30 CE) is a great prompt for discussing how we know what we know about art from antiquity-from a time before cameras, digital recording, and even printing presses. You might begin with some images of Ancient Etruscan art, noting that theirs was a related yet distinctive culture in Italy from 800-400 BCE, and not simply a prelude to the Roman. In the West, around Rome, successive waves of so-called “barbarian” invaders arrived as the Roman Empire fell into decline in the fourth and fifth centuries. Because the Byzantines spoke Greek, were officially Christians, and blended many cultures from around the Mediterranean, we might consider their culture distinct from the Roman. The timeline covered in this lecture begins with the period of Etruscan and Roman kings in the ninth–eighth centuries BCE, and moves through the Roman Republic (509 BCE) and the Roman Empire (27 BCE) to the reign of Constantine, and his transfer of the capital to Byzantium in 330 CE. As a secondary goal, teachers can trace a crucial evolution in architecture toward construction techniques that were cheaper and easier, and that shaped space in new ways. Previous lectures in the survey may have highlighted the relationship of art and religion in ancient societies, but this lecture-in addressing Republican realism, Imperial art, and civic building-looks at what happens when art is brought to the service of politics. Fragments of the Colossus of Constantine, Roman, c.Fresco, Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, Boscoreale, Roman, 50–40 BCE.View of Garden, Villa of Livia, Primaporta, Roman, c.Augustus of Primaporta, Roman, 63 BCE–14 CE.Pompey the Great, Roman, copy of an original made 50 BCE.Cerveteri Necropolis, Etruscan, ninth–third centuries BCE.Sarcophagus with Reclining Couple, Cerveteri, Etruscan, 520 BCE.Model of an Etruscan temple as described by Vitruvius, Istituto di Etruscologia e di Antichità Italiche, Università di Roma, Rome.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)